Quick, what do you think are the biggest obstacles to a more widespread adoption of telehealth by clinicians? Here are a few common wisdom favorites:

Technology 1: Clinicians don’t want technology to stand in the way of connecting with their patient.

Technology 2: Clinicians are frustrated by technology and don’t like to look stupid in front of patients when the technology does not work.

Too complicated: As a clinician it’s just easier to walk into an exam room (or to simply pick up the phone)

Spatial Disconnect: Clinicians state that they need to be able to examine the patient directly, not through a camera or other technology.

Reimbursement: Clinicians claim that telehealth visits are not reimbursed or not reimbursed at the same rate.

Patient Preference: Clinicians report that their patients don’t like telehealth and prefer to come into the office.

I actually don’t think it’s any of those!

Many of these arguments are red herrings and can easily be refuted. They are veiled excuses for being uncomfortable with change, not knowing where and how to learn, and, ultimately, they miss the picture of serving the needs of the patient.

From my vantage point with 15 years of telehealth implementation experience, the biggest indirect obstacle to a more widespread acceptance of telehealth by clinicians is the fee for service reimbursement that has warped the care delivery system.

“Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets” is one of my favorite sayings, and it is the fee-for-service system that presents the biggest obstacle not only to telehealth, but actually to achieving truly extraordinary health outcomes at a reasonable cost.

A Systems Engineer’s View of Creating Health

I’ll come back to the fee-for-service aspect, but allow me to focus for a minute on what’s actually important. Now I admit that I’m no clinician, so bear with me as I approach the art and science of medicine through the mind of a systems engineer.

From what I’ve observed in two decades in healthcare, the most significant predictor of a positive health outcome is the degree to which the patient is engaged in their care. Actually, let me rephrase that:

The biggest predictor of a positive health outcome is the degree to which the clinician succeeds in activating the patient to participate in their care.

A subtle but very important distinction.

In order for patients to get better, they need to contribute to their healing process in a multitude of ways that no one else can do for them:

- maintain a positive attitude and be an advocate for their health

- follow doctor’s orders regarding diet, exercise, and sleep

- take the prescribed medications and complete the requested lab tests and radiological exams

- communicate any questions or concerns that stand in the way of following the orders

- etc.

As many of us know from our own experience, these can be difficult to follow when one is not feeling all too well. Which is where the support of the patient’s clinical team is crucial to achieve a positive health outcome.

Introducing: Telehealth to the rescue

Despite the saying that “absence makes the heart grow fonder” it is actually “out of sight, out of mind” that is more accurate for most people.

As human beings, we crave connection. We trust those we are in close or frequent contact with (see the Stockholm Syndrome where captives over time empathize with their captors) and we trust those less, who we see infrequently.

While over the past decades the white lab coat with the stethoscope has lost its authoritative power, even as modern healthcare consumers we still rely on the expertise and experience of our doctors. But we can only do so, if we can access their expertise.

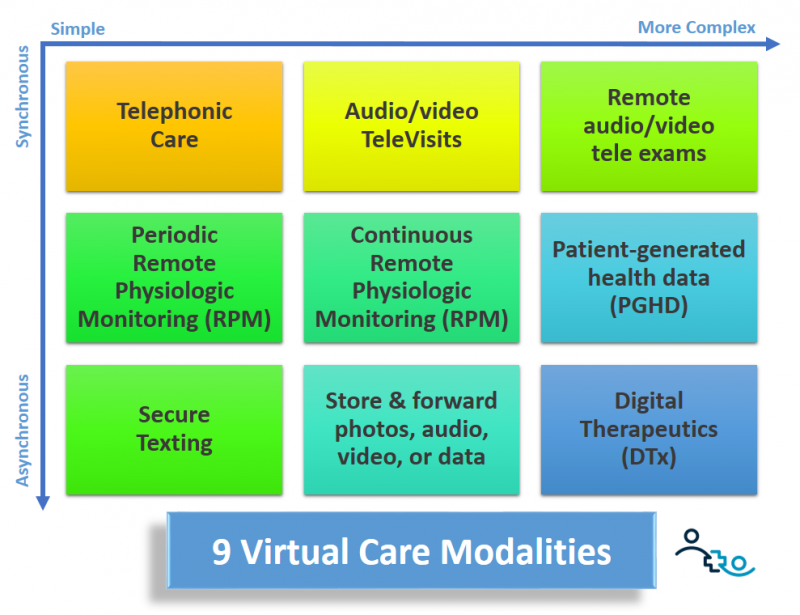

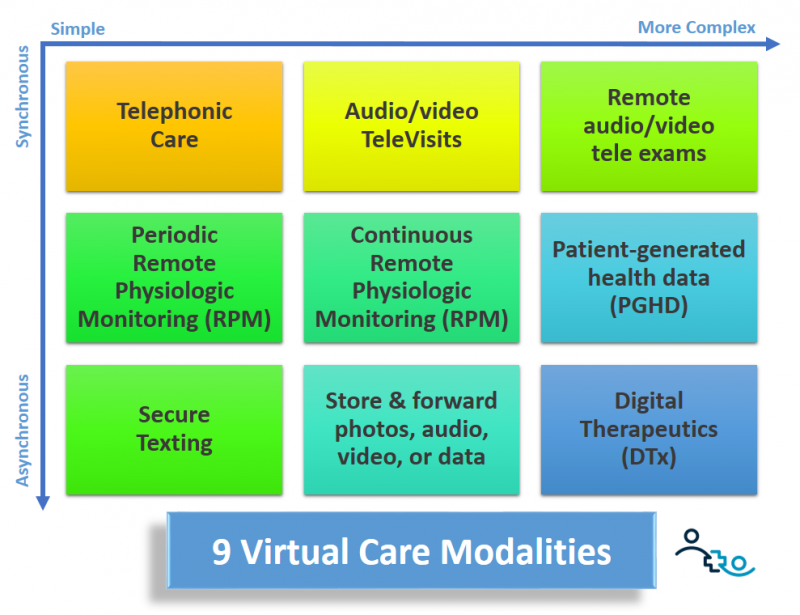

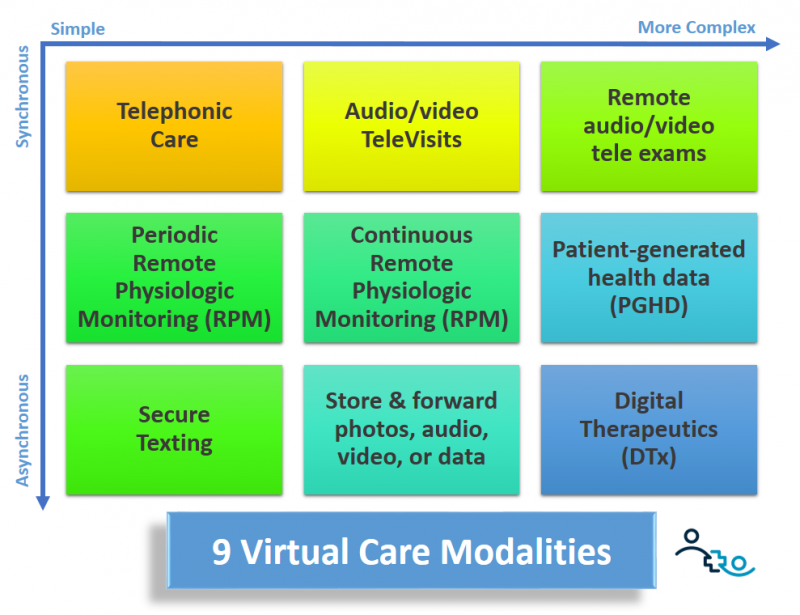

Telehealth has numerous modalities that can make it easy and quick to stay in touch with patients and to accompany them on their journey, without the need of an appointment or having to travel to see the doctor. Here are the main telehealth modalities:

TeleVisits — of course video visits are the gold standard of “care at a distance” as it allows the clinician to “observe” the patient “in their natural habitat”. Over video, with an established relationship, these check-ins can be as quick as a couple of minutes.

TeleExams — for conditions that require insights into a patient’s vitals or visual assessment, virtual exam tools (such as dermoscopes or stethoscopes) can provide good insights “at a distance”.

Phone Calls — a tried and tested (unpaid) tool of medicine for decades, a quick call is often what is needed in an ongoing, active patient-physician relationship.

Secure Messaging — with the increased acceptance and the asynchronous nature of secure messaging, conversations can take place at the discretion of both parties. Patients can send (non-urgent) questions at 3 AM and clinicians can answer when they start their day.

Remote physiological monitoring (RPM) — gaining insights into the patient’s history of vital signs is critical for the distant care of some conditions, especially chronic care.

TeleEducation — information is power and providing patients with curated and personally recommended resources about their diagnosis, their treatment, and how to live best with their condition are a powerful tool in activating patients’ participation.

Digital Therapeutics — while not strictly a direct connection between the clinician and the patient, guided therapy (as prescribed by the clinician) can take the place of direct interactions, especially if the app was customized by the clinician for the patient.

This is just a short list of the main virtual care modalities that can be used by clinicians to periodically and frequently stay in touch with patients to activate their engagement in their care.

But of course in a fee-for-service system these modalities will only be used by clinicians if it makes financial sense — i.e., if they are getting paid for spending their time on using those tools.

The Detrimental Effects of Fee for Service

First, let me start with a story.

Just recently, after experiencing months of worsening symptoms, my wife was diagnosed with a somewhat debilitating, uncommon autoimmune disorder. We got lucky by getting on the Neurologist’s schedule within a day due to a cancellation. The next appointment would have been 4 weeks out and my wife’s condition had been getting progressively worse.

The prescribed medication alleviated some of the symptoms, but, newly diagnosed, we had questions. Many questions. But the next available appointment was 6 weeks out. After a few exchanges between my wife and the neurologist, he disabled the messaging capability, asking her to call his nurse; he couldn’t answer her questions through messaging any more.

My guess? A policy that limits the amount of time clinicians can spend on answering portal messages vs. serving appointment slots paid for by the fee-for-service model.

The piece of advice given by the nurse? If your condition worsens, go to the ER — presumably because they could not see her until the next available appointment slot.

The frustrating thing: we had learned of at least three other medication and outpatient treatment methods, but without another (fee-for-service paid) consultation, the neurologist seemed unable or unavailable to engage in further clinical guidance. Frustrating!

Now, let’s do a little thought experiment: if you were a physician with a small patient panel and one of your loved ones gets sick: how often would you check in on them and what means would you use to do so? My bet is that messaging, video calling, emailing, sending links to videos, checking the blood pressure history in their app, etc. would all be modern tools that you would employ to provide the best care for your loved one.

Isn’t that the level of care we should make available to everyone?

Death to Fee-for-Service!

By paying for activities vs. paying for positive outcomes, don’t we have it all backwards?

My wife’s neurology office does not care whether my wife goes to the ER or not. Financially speaking it does not cost them anything. But it would cost them if they provided unpaid clinical advice through the messaging portal or over the phone. So they recommend the ER.

As I said: “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.”

Ultimately, the sad reality is that the Fee-for-Service system robs the clinicians’ decision making power. Their hands are often tied and they cannot do what would be best, but have to do what pays the bills.

So here’s to a world without fee-for-service, to the growth and expansion of the various value-based payment systems that are being rolled out today, albeit in numbers still too small.

Here’s to a future, where clinicians can do what’s best for the patient, not what they get paid for.

Because when Fee-for-Service is finally dead (though it won’t be missed), we can finally let Telehealth lose as the Clinical Savior to care for patients where they want, when they want, and how they need.

I’m curious: what percentage of your patient population is cared for under a value-based care arrangement? Drop me a note!

To receive articles like these in your Inbox every week, you can subscribe to Christian’s Telehealth Tuesday Newsletter.

Christian Milaster and his team optimize Telehealth Services for health systems and physician practices. Christian is the Founder and President of Ingenium Digital Health Advisors where he and his expert consortium partner with healthcare leaders to enable the delivery of extraordinary care.

Contact Christian by phone or text at 657-464-3648, via email, or video chat.