Language is very powerful and certain words can convey a number of different meanings depending on the context and the situation. Words can hurt (as in “calling names”) or they can heal (as in “words of affirmation”). Words are almost always used by those in power to defend their power. Masterful leaders use words to accomplish their objectives – but so do dictators and autocrats.

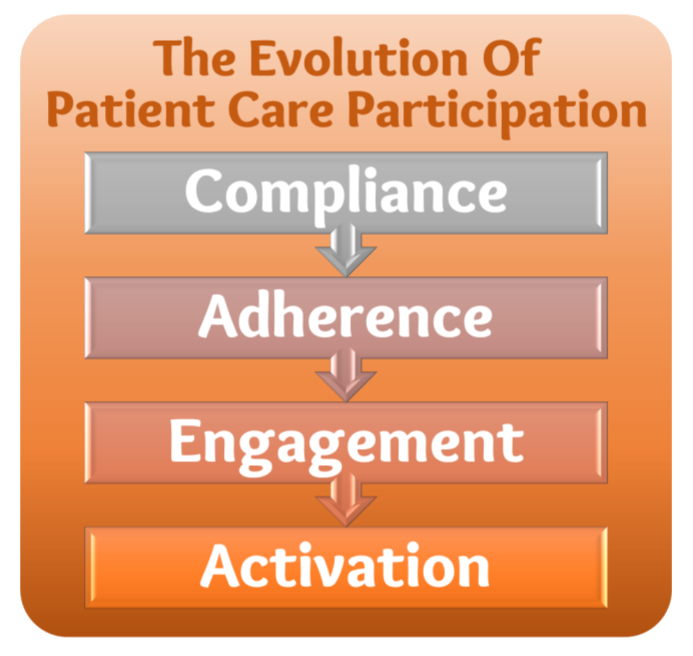

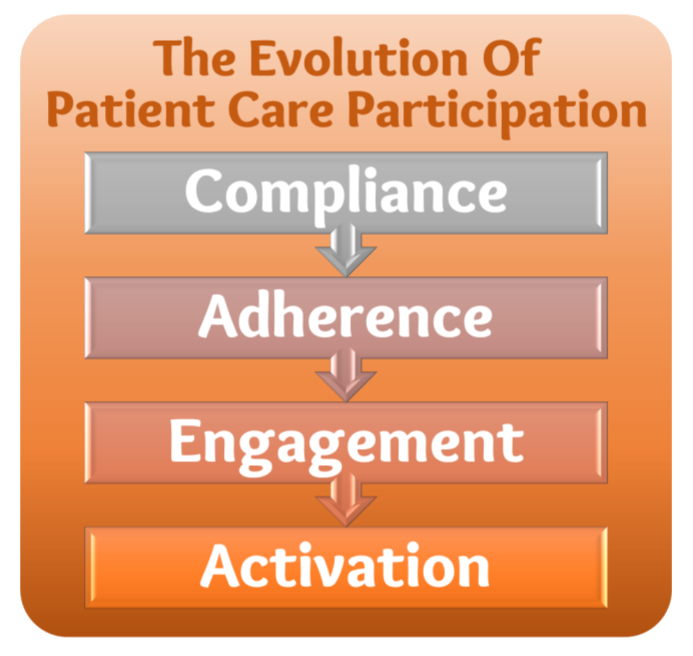

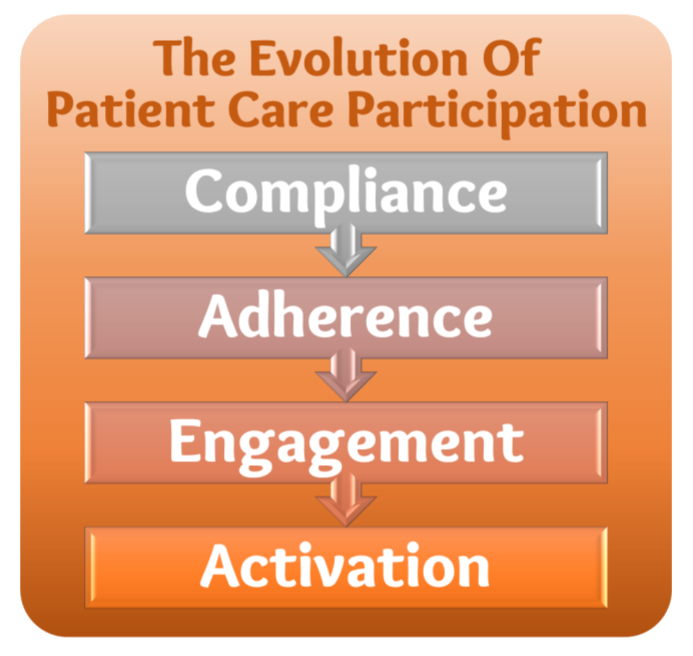

Patient Compliance

When I first entered the healthcare world at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota in the early 2000s, I came across an expression that I found quite strange: Patient Compliance.

I had just moved to the US two years prior and was still vigorously studying the English language and American expressions and trying to understand all of its nuances. Having encountered the word “compliance” in other circumstances (as in: following orders given by the authorities or obeying the rules), it seemed to be at odds with my fresh, naïve view of healthcare. I guess my image of “healers” and “helpers” clashed with the notion of “order givers” and “rule makers”. Why were patients supposed to do as told, “or else”?

Of course I quickly came to understand that most rules were designed to protect the patient (“don’t get out of bed — because you have an IV in your arm!”) and to help them heal or at least prevent a deterioration of their condition.

Over time, as “treatments” and “care plans” became more and more about making lifestyle changes (sleep more, eat less, exercise more frequently) and the prophylactic or health maintenance consumption of medications. Here, the disbelief and frustration seemingly conveyed in the phrase of the patient “not being compliant” seemed arrogant and did not show much empathy and absconding responsibility.

If the doctor tells the patient to take a pill daily and the patient does not take the pill, then who has failed — the patient or the doctor? I’d say definitely the doctor. And maybe also the patient. But the word “compliance” is pre-judging the patient and not taking the circumstances into consideration.

Maybe the pills gave the patients side effects they did not know how to deal with and were afraid to ask about. Maybe they simply forgot. as the habit of taking medication daily is not second nature to most. Or the medication is too expensive. Or maybe the medication was not making them feel abny better (or worse), so they stopped taking it.

In any of these scenarios, the clinician failed the patient in explaining the side effects, in following up with the patient after a week or two, in making sure that the patient understood the benefits of the medication, etc.

Overall the world “compliance” reeks of arrogance and conjures up images of demi-gods in white lab coats “knowing what is best for the medically-untrained patient”.

But after a few years in healthcare, I came across a new term:

Patient Adherence

Putting on my “English as a second language” hat for a moment, my first association is with “adhesive”, i.e., something that sticks. I guess “adherence” is about “sticking to the rules” and it sounds a bit less harsh and less dictatorial as “compliance’.

When a “patient is not adhering to the care plan”, then it linguistically leaves the option open to change the care plan vs. to blame the “non-adherence” solely on the patient.

Still the concept of patients having to “adhere” to a plan still misses the opportunity to have patients actively participate in their care.

Which brings us to the next term, that I first heard in the mid- to late 2000s.

Patient Engagement

This new term really shifted the gestalt of the patient/physician relationship from one of a “master and servant” to co-conspirators in figuring out the best approach to solve the problem at hand: how to improve the patient’s condition.

What clinicians, I think, realized is that ultimately the patients are the ones who have to put in most if not all of the work: Take the pills. Watch your diet. Go to physical therapy. Undergo the surgery. Have that CT scan. Etc.

Almost none of those activities involve the treating clinicians — but they all involve the patient. The goals of the care plan thus can only be achieved if the patient is engaged in the design of their care journey. And it becomes the clinician’s responsibility to get the patient engaged – and not to simply expect the patient to comply with a plan they developed without the patient’s involvement.

Patient Activation

Finally, over the past few years, I have occasionally heard the term Patient Activation. While it is similar in concept of engagement — the patient actively involved in the process — it is more active and less passive than “engagement”.

The connotation of Patient Activation to me is one of the patient being empowered to take charge, to be proactively involved in doing what it takes to get well and to stay well. The patient is motivated, alive, activated out of sleep mode.

With this amount of “transformation” in a patient’s attitude — after all, being sick or diagnosed with a severe illness can be very depressing — the responsibility now lies with the whole care team to provide education, answering questions, jointly figuring out what works for the patient and what does not. This process is obviously much more lengthy but in the long run can save hundreds of thousands of dollars in avoided treatment costs.

As the saying in the quality world goes: “If you don’t have the time to do it right the first time, where do you take the time to do it over?”

Beyond Engagement and Activation

In this evolution of terminology I actually have a recommendation for an even better term: Patient Commitment. It stems from the joke of a chicken and pig wanting to open a restaurant, which the chicken suggests should serve “Ham and Eggs”. To which the pig responds: “No way! You’ll be involved — but I’ll be committed”.

The term commitment, similar to activation, recognizes that the care plan must have the buy-in by the patient. They must have the desire to follow the things set forth in the plan and pledge commitment to following the plan – and to ask for help if they can’t.

Using Telehealth for Patient Activation

Ultimately the engagement and activation of a patient in their care requires influencing behavior. And it’s very difficult to change behavior when all you have is 7-12 minutes in a visit every 1-3 months.

Telehealth — “Delivering Care at a Distance” — provides a convenient way for many more touchpoints to support, inform, and educate patients in order to have them actively participate in the design of the care plan and in following the care plan.

This can include many telehealth modalities, for example secure messaging/texting to check in with the patient, a quick phone call to clarify something, a brief video visit for medication reconciliation, the use of remote physiological monitoring devices to provide feedback on vital signs managed by the medications, sharing educational videos, reminder apps, etc.

Telehealth thus can, when wielded appropriately, serve as a powerful patient activation tool. Even the care plan can be jointly documented. I’m sure there’s an app for that.

Do you want to brainstorm with your clinicians and me how to leverage telehealth in your organization? Contact me with the links below to schedule a brief call.

To receive articles like these in your Inbox every week, you can subscribe to Christian’s Telehealth Tuesday Newsletter.

Christian Milaster and his team optimize Telehealth Services for health systems and physician practices. Christian is the Founder and President of Ingenium Digital Health Advisors where he and his expert consortium partner with healthcare leaders to enable the delivery of extraordinary care.

Contact Christian by phone or text at 657-464-3648, via email, or video chat.

Leave A Comment