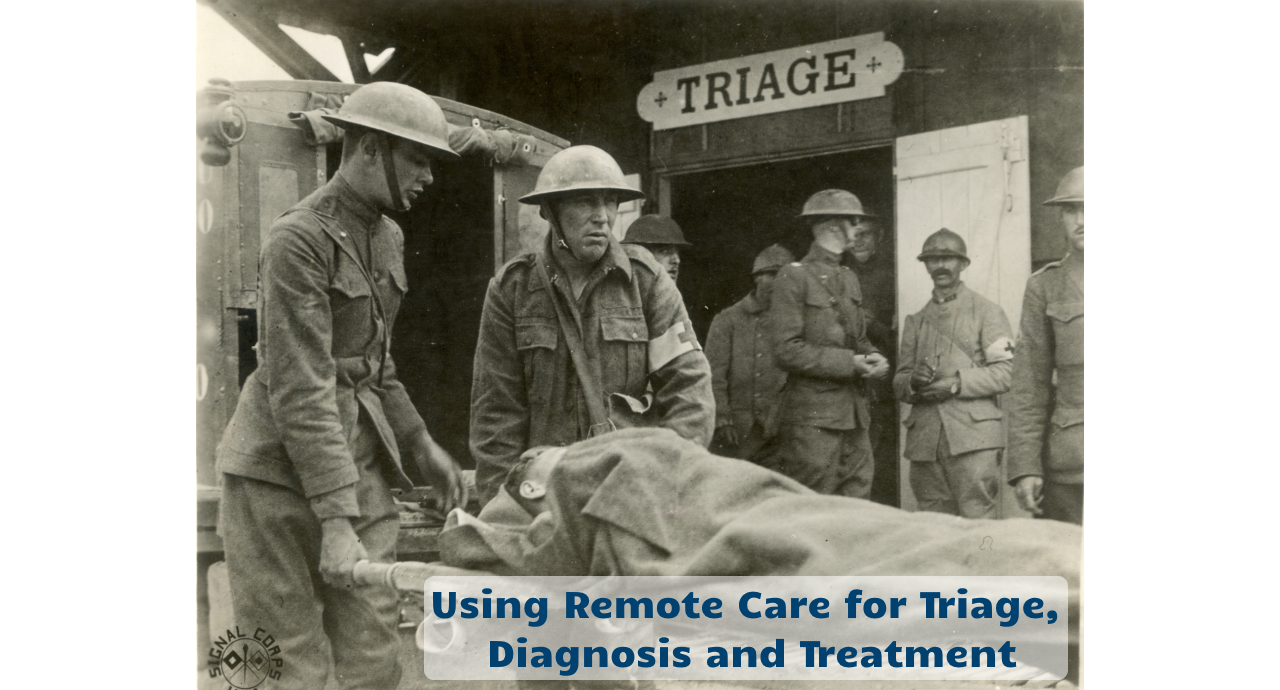

Almost exactly 100 years ago, the term triage was introduced into the common vocabulary of modern times. The stem of this word, ‘trier’, is of French origin and means ‘to separate, to select, to sort’. The concept of triage was developed on the battlefields of World War I and in the context of the Spanish Flu epidemic, of 1918.

So it’s only fitting, 100 years later, that we will now have to make full use of excellent triage processes in light of this global pandemic. The mounting pressures on the health care system will require a much different approach from “business as usual’ and even telehealth is no panacea.

My pragmatic definition of triage is to match the limited resources to the most urgent and pressing needs.

During World War I, hard decisions had to be made when a field hospital with limited resources was presented with an overwhelming number of soldiers needing medical attention. The field hospital staff receiving the injured soldiers had to quickly decide who was going to receive what level of care and who was going to be given access to the precious resources of surgical beds and surgical teams.

When you had to decide between a lightly injured and a severely injured, the decision was easy. What was much more difficult is to make a decision between two severely injured people with only one surgical team available. Here a decision had to be made which one of the two is less likely to survive and thus should not receive the care.

With the coronavirus pandemic, we are dealing with two major challenges that are very different from the situation that faced the staff in the field hospital in World War I, yet the principle of triage still applies.

The first challenge is that the Coronavirus is highly infectious, unlike the illnesses presented at the field hospital during the war. Thus, the goal in triage for our crisis has to be to do everything possible to keep those potentially infectious away from other, healthy people. The high contagiousness of the coronavirus also requires to keep the suspected patients away from the health care workers, lest they get infected.

What makes the situation even more threatening, is that most people show no symptoms of the disease for at least 5 if not even up to 25 days, thus making isolation of anyone not tested a high priority.

The second major challenge of this health crisis is that we know with certainty that a high number of health workers will not be able to show up for work in the near future. There are three reasons for that. Firstly, with the country-wide school closings, parents with school-aged children need to stay at home. Secondly, a high number of health care workers, even though they may not be infected, will be asked to self-quarantine due to a known exposure to a coronavirus-infected patient.

Thirdly, we will have a percentage of healthcare workers who will actually get infected and show symptoms of the disease. For perspective, during the SARS epidemic, up to 25% of the people falling ill were healthcare workers.

The primary solution to all of these challenges is a combination of thoughtfully defined and widely-understood processes and protocols that must be followed judiciously by staff and patients to prevent the further spread of the disease and to prevent the strain on the healthcare system caused by a workforce shortage or workforce absence.

Within the processes and protocols, the use of technology to remotely deliver care via video, phone or via text messaging is one of the best solutions to keep people from becoming infected. In the third wave of this crisis, these technologies will also allow the healthcare workers to stay involved in patient care, even when they are confined to their own home.

Please note that I very consciously chose the phrase “to remotely care” versus the obvious phrase of conducting telemedicine. The reason for that is that we need to establish these capabilities very quickly, which means that we will have to cut corners with regards to properly setting up these distance care services.

As I’ve written about extensively, implementing telemedicine correctly and appropriately requires a multitude of resources, workflows, technologies, training and support. But this is obviously not the time to design for perfection while the disease is spreading rapidly. This is the time for pragmatic solutions that give patients access to basic care and that will allow us to quickly triage each patient into the most appropriate and safest care process.

The first priority has to be to set up processes that will quickly allow us to triage each patient to the right level of care, whether that is home care via video or a drive-through testing station in a tent or an in-person visit in an isolation room with personal protective equipment (PPE).

So, here’s the quick process that you can go through in a matter of a day or two without cutting too many corners or endangering patient and staff safety.

First, clearly identify the focus of your remote care process. You should look for those demands on your systems that are causing the most strain. Is the demand coming from existing patients wanting to avoid coming in? Or is it people calling because they are concerned that they may have the corona Corona virus? After you selected one specific scenario, focus on one specific patient population and focus on the desired outcome. Is it triage (which I highly recommend to be the focus of your first processes to define) or is it diagnosis or care?

Next (2), define the workflow from the patient’s perspective, from the providers perspective and from the Allied Health staff’s perspective. After you’ve identified the experience you would like patients, providers and staff to have, work with your technical team or a vendor-agnostic telehealth technology expert (like Ingenium) to select the best technical solution that helps you to accomplish the objectives of your workflow.

But do not design your workflows around what technology is available. Rather select the technology option based on your definition of excellent, safe care.

In parallel (3), have your billing, compliance, and legal staff research the necessary policies around reimbursement, licensing, consent forms, etc.. Note that all these three areas are currently changing on a daily basis.

Now (4) you can work on the appropriate and sufficient training materials for the processes, policies and technology. Remote care is not rocket science and a training session can typically be accomplished in 20 to 30 minutes. But the training should not solely focus on the “webside manners” or the use of telehealth technology. It needs to include the training on the bigger picture of the different workflows and the policies that need to be adhered to.

Lastly (5), for the first set of remote care visits immediately debrief with the provider and staff and collect suggestions for improvement of the processes, the technology and the training materials or to provide additional training as necessary.

Finally, it is crucial that you define a set of quality metrics that you can track to ensure that the remote care delivery is achieving its intended objectives and that provides you insight into the performance of the processes and the technology.

In the upcoming weeks, I will continue to write about using distance care technologies to triage, diagnose and treat our patients. In the meantime feel free to drop in to one of our telehealth expert sessions at https://tiny.cc/ing-th-cov19-sessions.

To receive articles like these in your Inbox every week, you can subscribe to Christian’s Telehealth Tuesday Newsletter.

Christian Milaster and his team optimize Telehealth Services for health systems and physician practices. Christian is the Founder and President of Ingenium Digital Health Advisors where he and his expert consortium partner with healthcare leaders to enable the delivery of extraordinary care.

Contact Christian by phone or text at 657-464-3648, via email, or video chat.

Leave A Comment