Last week I had an interesting, enjoyable experience. When asking our 13-year old’s primary care provider for a referral to an allergist for her eczema and presumed heat rash, we were told that the first visit would be via telemedicine, and that a visit in the office would only be needed if necessary.

Interestingly, the single-practitioner is located only 10 minutes away from where we live and the physician was working from his office, presumably in his clinic.

The gathering of my daughter’s medical history, the review of current prescription ointments and over the counter creams, and the exam of her eczema in the elbow pits — or, the cubital fossa, as he taught us — was patient, unrushed, and thorough. Over the course of a 40-minute mid-morning visit he reviewed with her, with my wife, and with me our questions and our concerns.

Via the chat function of the EHR-embedded video platform he provided the spelling of medications and conditions and, demonstrating great webside manners, asked for our patience, as he typed in some notes and marked some fields in the medical record.

His unhurried manner revealed, in the last 15 minutes of the visit, that my daughter also has an occasional allergic reaction to her bunnies and her bunnies’ hay, providing him with more insights and details as to her medical history.

In this much longer than usual conversation, we also covered my and my wife’s history of allergies (hay fever in my youth in my case and heat rashes in my wife’s case), completing the picture of my daughter’s allergy-related history and her family history.

A Satisfying Experience

Having worked in telehealth for 20 years, I’d have never guessed that a physician, especially one with seemingly more than three decades of experience, who was asked via referral to consult on a teenager’s skin conditions, would have preferred (or almost insisted) to see her via telemedicine first.

Now, he did offer to see her in the office — but not for further physical examination, but to perform some skin-based allergy tests on her, presumably to test her reactions to pet hair and grasses.

Overall, it was a very satisfying experience — and very convenient, too. We did it from the comfort of our home, I joined between two meetings on a very busy day, and no fossil fuel was wasted for transportation.

The advice given was solid, the plan of action was clear and I felt more knowledgeable about some parts of human anatomy and the best approach to react to a flare up of my daughter’s condition.

The Growth of Virtual First

Since the beginning of the decade, before Covid, I speculated that within 10 years’ time, “having a doctor visit” will mean to have partaken in a video visit and that the oddity of having to go to a clinic to see the doctor in person in their office will bestow upon you bragging rights at the next neighborhood get together: “You won’t believe what I had to do yesterday! I had to go to this clinic, and sat in one of those waiting rooms before I was led into a room where I had to wait again for my doctor to see me.”

Now, after this experience with my daughter, I’m even more sure than ever that virtual first is the future of medical care as we know it. Of course not for everything – but for mostly everything, at least the visit part. The days of the system by which we expect clinicians to be in the same room with the patient, are counted.

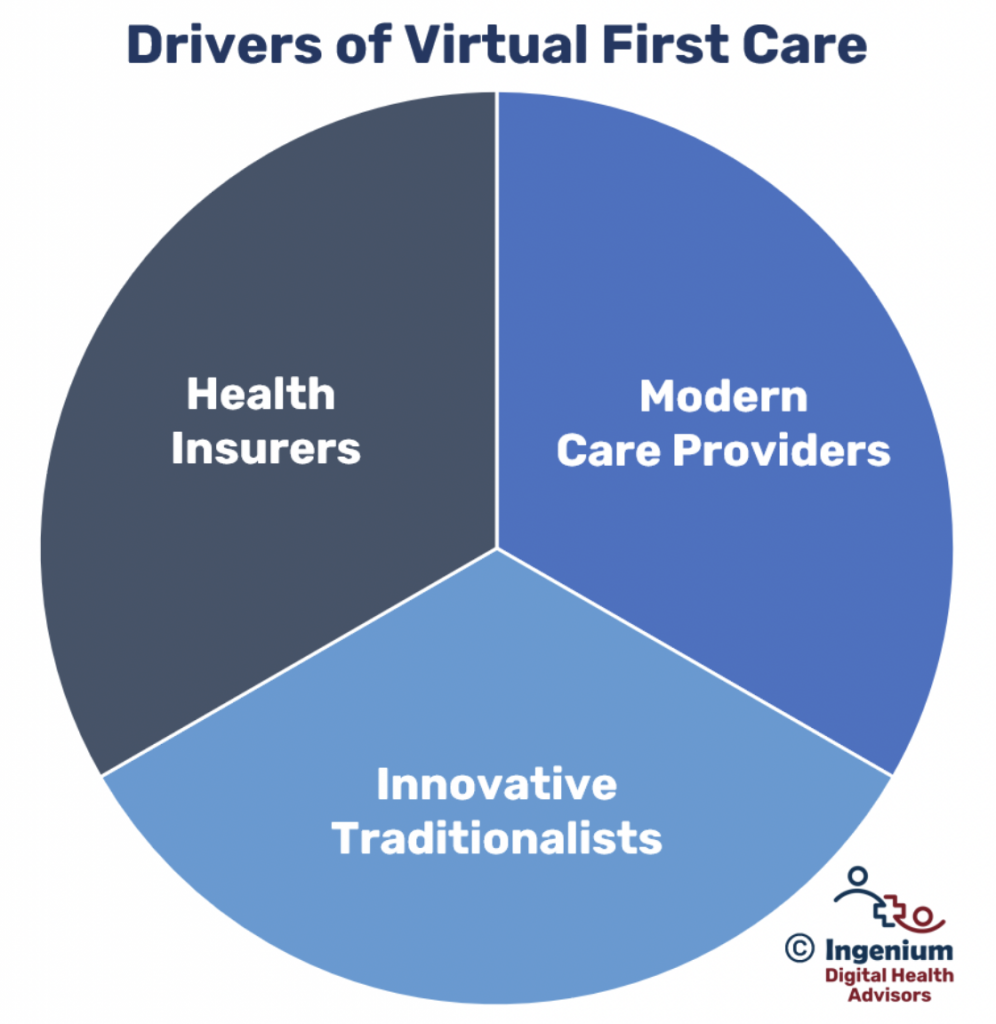

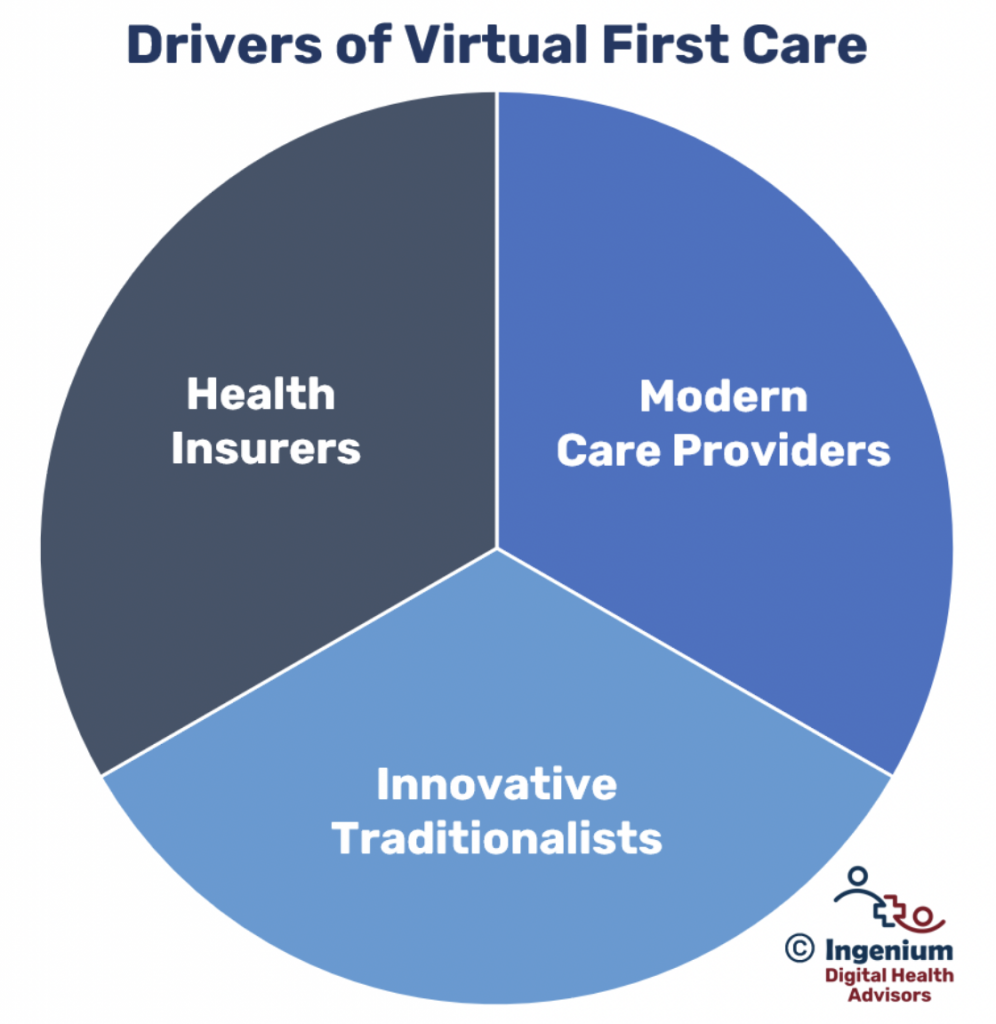

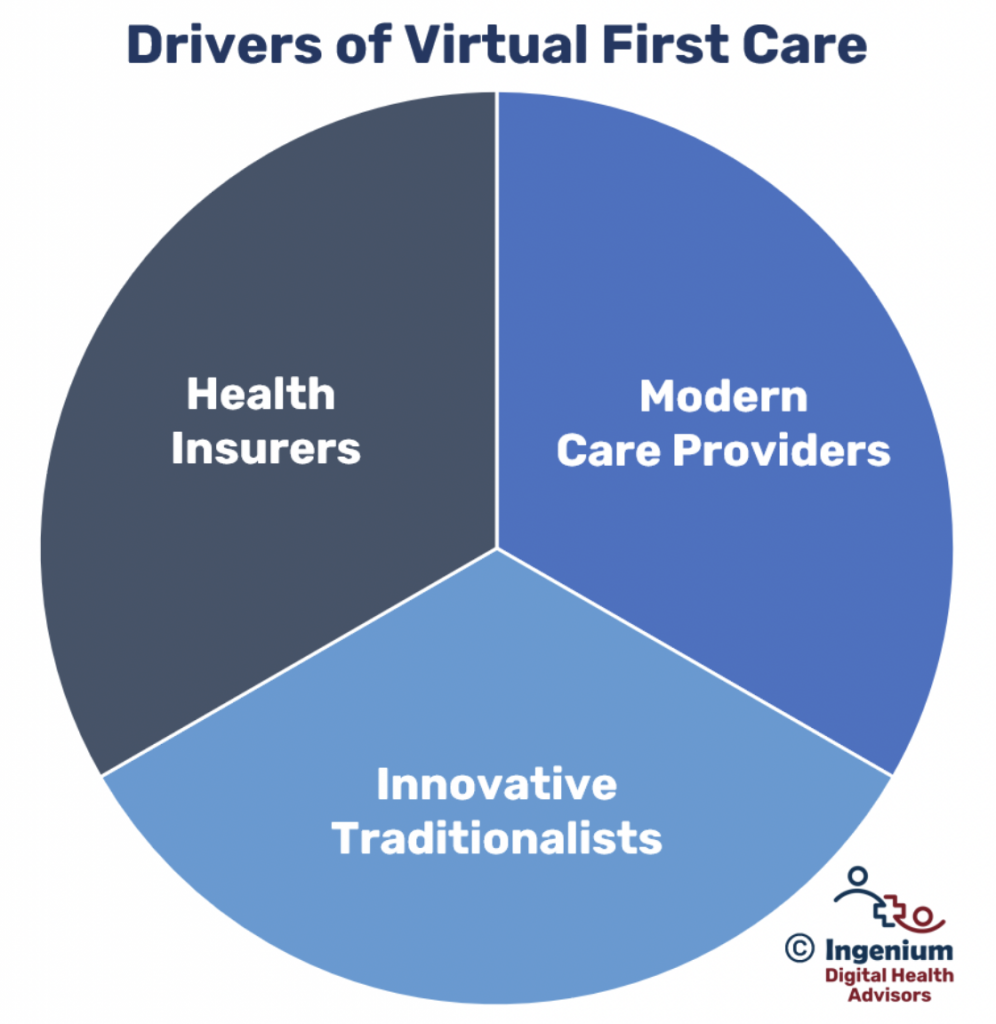

Virtual First, of course, is not a novel concept practiced solely by this allergist. Many of the modern, non-traditional healthcare providers founded in the past 10 years have virtual first (or virtual only) at the core of their business model.

In 2021, Jama published an article about the insurance-driven models of “virtual first” spurred by the availability growth of the many “virtual only” companies like AmWell, Doctor on Demand, Wheel and others. The value proposition presumably being that quicker access to (virtual) care can reduce the more costly use of urgent care, the use of the emergency room, or the delay of care resulting in disease progression.

In another example, Amazon in early 2023 acquired One Medical, which provides both virtual and in-office medical services — a modern breed of healthcare organization that delivers its care through a virtual first model directly serving consumers and more than 8,500 self-insured companies.

In recent years, a few of the innovative traditional healthcare companies, e.g., Jefferson Health, also started promoting virtual first access to care, reacting to the desire by the modern healthcare consumer to prioritize convenience over unquantifiable quality.

The Barrier to Virtual First is not Clinical

As many of these approaches to provide effective, profitable care are demonstrating, the barriers to virtual first care are not financial and they are also not clinical.

The repeated argument by the naysayers is that the quality of care is not and cannot be as good as in person care.

Having been introduced to high quality care at the inventor of the unified medical record, the Mayo Clinic, I agree that the fragmentation of care, the absence of a more or less complete medical history (exacerbated by one off visits with random physicians), and the lack of care coordination all can result in suboptimal care.

But that is not a downside of virtual care, per se. Patients, seeking convenience, can treat themselves with over the counter medications, seek out medical cannabis, visit the nearest urgent care facility or utilize the ER for their urgent or primary care or even chronic care needs. Even though all of these visits occur “in person”, it’s still a very fragmented care experience that ultimately does not help the patient.

Another way to dispel the blanket criticism of virtual care’s clinical quality is to ask any clinician: “When was the last time your diagnosis relied solely on a physical exam that you could not have administered via a video visit?” In most cases, a full diagnosis is backed by lab tests or radiological exams. In some cases, a more thorough physical exam serves to confirm the experience-based diagnosis formed based on the patient’s description of their symptoms and/or health and family history.

Can certain aspects of a patient’s condition be missed in a virtual environment? Yes, of course – just like they can be missed if the patient presents in person.

Thus, for now, the barrier to the widespread adoption of virtual first is not clinical. No, it’s a traditional mindset, a fear of the unfamiliar, a resistance to change, and an unwillingness to more seriously examine one’s objections.

100% Telehealth does not mean all the care is virtual

For me, 100% Telehealth means that (1) if the patient wants it, (2) if they have the technical capabilities, and (3) if it is clinically appropriate, a virtual visit should result 100% of the time.

But that does not mean that I advocate for care to be delivered virtually all of the time.

Many times patients (myself included) don’t mind or even prefer to be in person. Many patients do not have good connectivity, or adequate technology, or even sufficient digital literacy.

It does mean, though, that telehealth should be offered to patients as an option virtually (!) all the time, except, of course, if the patient’s symptoms require a call to 911 or a more thorough examination.

Is your executive and clinical leadership ready to push for this mindset shift?

When you’re ready, Contact me for a complimentary conversation about the approaches your clinic or hospital must take to increase clinicians’ and staff’s willingness to offer virtual care first.

To receive articles like these in your Inbox every week, you can subscribe to Christian’s Telehealth Tuesday Newsletter.

Christian Milaster and his team optimize Telehealth Services for health systems and physician practices. Christian is the Founder and President of Ingenium Digital Health Advisors where he and his expert consortium partner with healthcare leaders to enable the delivery of extraordinary care.

Contact Christian by phone or text at 657-464-3648, via email, or video chat.