If you’ve been reading my Telehealth Tuesday column for a while, you know that I always urge my readers to pay particular attention to the various workflows leading up to and following the actual telemedicine visit.

By now you should recall that there are the 7 Thworfs – Seven Telehealth Workflows that define what should happen before, during and after a telehealth visit.

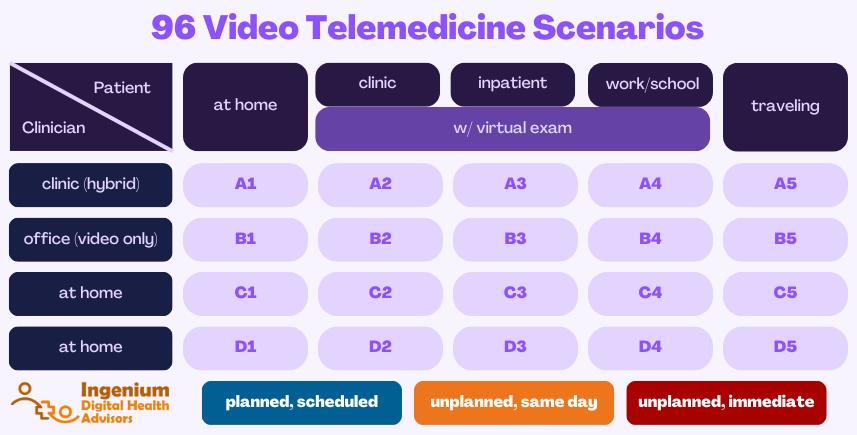

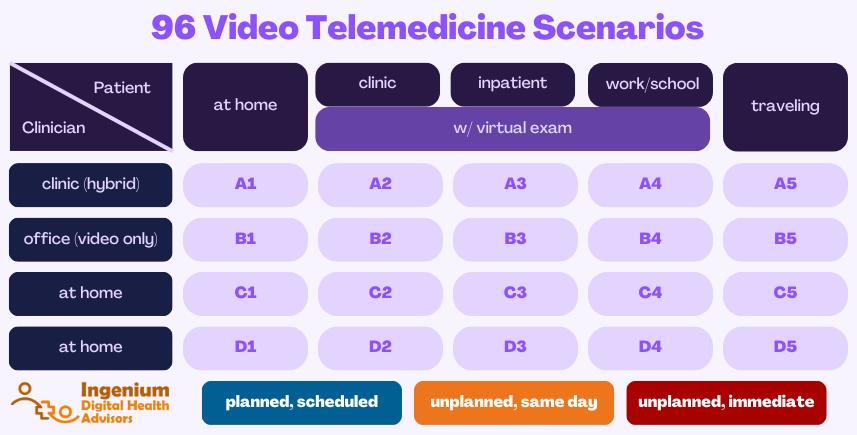

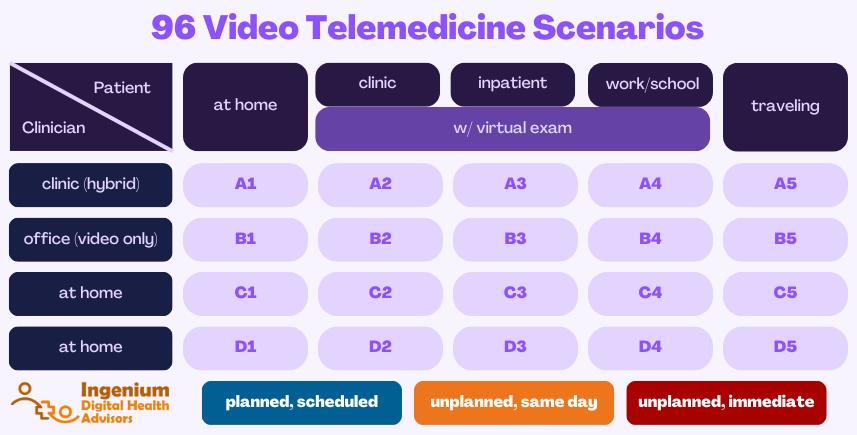

But did you realize that there are about 96 very common scenarios for telemedicine? And that for each of them a different combination of suitable workflows have to work together to create a stellar experience for clinicians and patients alike?

(that’s what happens when you let an engineer loose onto healthcare delivery 😉)

How did I come up with 96? For starters, the patient can be in one of 5 common locations:

1. at home

2. in a clinic

3. in an inpatient setting (including the hospital, ER, or nursing home)

4. at work or at school

5. traveling

And each of those locations will require a slightly (or significantly) different workflow.

In three of those five locations (clinic, inpatient, or work/school setting), patients may also have access to virtual exam tools, such as a digital stethoscope, video otoscope, or video dermatoscope.

Secondly, the provider conducts telemedicine from four typical locations:

A. from a clinic in a hybrid environment mixed with in-person care

B. in an office setting, providing only virtual care

C. in a home office setting

D. traveling

Lastly, telemedicine visits can be scheduled in three different ways: planned/scheduled (P), unplanned/same day (S), or unplanned/immediate (U).

Simple math ((5+3) × 4) × 3 results in 96 different scenarios, as described in the table below:

To help you modify or design the optimal workflows and policies for each scenario, here are some considerations:

Considerations for Patient Locations

1. The Patient is at Home: This is obviously one of the most common scenarios and, as we experienced during the Covid-19 public health emergency, brings with it its unique set of challenges. For starters, as a healthcare provider you have very little control over the patient’s connectivity, the configuration of their technology, or their digital literacy.

Your best approach is to institute a Telehealth TechCheckSM that before their first video visit walks the patient through the various steps, so that your providers can have a smooth experience.

2. The Patient is at a Clinic: This is another very typical scenario that many of our clients are using. Here, the patient checks in at a clinic location that is closer to home then the location where the provider is located. For example, this can be used for visits with psychiatric nurse practitioners who often need to cover a wide geographic area. Other common examples are visits with subspecialists, or when a location does not have a full-time clinician (or the sole clinician is out for the day).

The most common challenge with this scenario is to synchronize the workflows between the patient location and the provider location.

3. The Patient is an Inpatient: With this set of scenarios, I’m combining patients on the hospital floor, in the ER, or in a nursing home. Aside from having to define the workflows for who is going to set up and initiate the video call, this scenario also requires a different set of technology on the patient end, which is often a mobile cart in a hospital or ER setting, or it can be a stationary unit in a room that the patient is led to. Similar to the “at a clinic” scenarios, synchronizing workflows between the two sites requires good planning and good communication tools.

4. The Patient is at work/school: For this scenario, we are assuming that there is a designated, established telehealth room that is being used for the visit (vs. the employee merely locking themselves into a meeting room and then using their electronic device). Specific notable considerations here include schedule coordination (making sure the “telehealth room” is not double booked) and taking extra precautions to protect the privacy of the patient – not just through soundproofing but merely by “giving away” that you have an appointment by using the designated space.

5. The Patient is traveling: In many ways, this scenario is the same especially if the patient is traveling within the same state. If the patient is out of state, check your state laws (and the “host state’s” laws) regarding the ability to treat an established patient that is temporarily “crossing state lines”. As you know, most states require you to be licensed in the state where the patient is located.

Considerations for Virtual Exams

In a clinic setting, an inpatient setting or in a designated telehealth space that is staffed with medical support staff (e.g., a nurse or a medical assistant, MA), the clinical quality of primary care and subspecialty telemedicine visits can be greatly enhanced through the use of virtual exam tools. That can include a digital stethoscope to assess heart and lung sounds, video otoscopes (especially helpful in elementary school settings for diagnosing the frequently occurring ear infections), or video dermatoscope (great for skin rashes or wound assessments).

The primary differences for these scenarios lie in the training that is needed for the “tele presenter” to operate the virtual exam tools and provide diagnostic quality images; in the definition of the communication protocol for the clinician to direct the remote exam; and, oftentimes, establishing a technical interface that allows the clinician to store images, video, or sound recordings in the patient’s EMR.

In addition, when clinicians are working from home or are traveling, their system needs to be set up with the appropriate software to “see/hear” the remote exam tools.

Considerations for Clinician Locations

A. Clinician is in a Clinic, providing hybrid care: This most common scenario means that clinicians are seeing patients in person and occasionally are switching to video visit. For some providers, especially those often running behind schedule, this “context switching” can be very disorienting and one solution is to “batch” multiple video visits together, e.g., in the afternoon. For more information read my description of the block cheese and Swiss cheese model of scheduling.

B. Clinician is an Office, providing virtual care only: This is a scenario practiced by some telemedicine companies (though many have their “office” set up at home) but also some “traditional” healthcare providers. Years ago, Mercy Health established a virtual hospital that has no patients. Every morning doctors, nurses, and other clinicians would enter the building to treat patients remotely all day long.

Since there is no “context switching” this scenario is very acceptable to most clinicians. When the aforementioned “block scheduling” model is taken to the extreme so that a full day is set aside for telehealth visits, the outcome is basically the same as this scenario.

C. Clinician is at Home: In contrast to setting up a permanent home office (which would be the same in principle as the last scenario), this scenario focuses on the clinician who is occasionally working from home — e.g., during an infectious illness (such as Covid) or even during a more prolonged leave of absence.

The key here is to work with IT and your Rock Star Telehealth Coordinator to make sure that the clinician’s setup is technically secure and acoustically private and that it presents a professional space with a proper background and lighting.

D. Clinician is Traveling: While most limitations on telehealth are put on the patient’s location, in most cases, the clinician could be located anywhere. There are some states (e.g., New York) that require that also the physician is residing in the state when performing telehealth, but for the most part, the clinician’s location does not prohibit billable services.

The primary challenge here is to provide the clinicians with sufficient guidance on how to properly use their system/setup when traveling – from proper lighting and proper background, protecting the privacy of patients is key.

Considerations for Scheduling

The final set of considerations focuses on the ways telehealth visits are scheduled. Is it a last-minute urgent care or a pre-scheduled regular visit? Or does the patient need to be “seen” yet today?

Prescheduled Visits (P): Obviously for most primary, behavioral health, and subspecialty care this scenario is the most common way that visits are scheduled. The benefit of this type of visit is that it allows for a Telehealth TechCheck℠ to be conducted (if the patient is indeed at home) if this is the patient’s first time doing a video visit. Otherwise, this is no different then a pre-scheduled in-person visit.

Unplanned, Same-Day (S): This scenario is quite common in primary care, when patients are calling the clinic with acute but not severe symptoms and need to be seen today. This scenario also often plays out in acute cases in schools, and most providers are not available on short notice.

The key to success here, especially in a primary care setting, is to agree on and clearly communicate to front office staff which types of chief complaints are NOT appropriate for a video visit (and either need to be redirected to 911 or be seen in person).

Unplanned, Immediate (U): Most traditional outpatient clinics are not set up to handle urgent video visits (though urgent inpatient visits by walk-ins are quite common) and this scenario is relatively rare. For Urgent Care centers, however, this is the “usual norm” although many visits are also simply “same-day” vs. “immediately”. The key to making this type of scenario work is to set up a proper triage team that can take care of the patient until a provider is available.

A Few Examples of Common Scenarios

Now that we’ve built out the (5 + 3) × 4 × 3 = 96 scenarios. Here are just a few common examples:

- The most prevalent in a traditional outpatient healthcare setting is obviously A1-P: Clinician in a clinic, patient at home, having a pre-scheduled visit.

- Very common in elementary schools is A4-S: a same-day appointment with a clinic-based clinician, oftentimes with an exam element mixed in.

- The “bread and butter” of telehealth companies such as Teladoc or AmWell are B4-P and B4-U, with many clinicians working from home in a professionally set up office, serving

- Prior to Covid, I’ve implemented dozens of A2-P scenarios: patient presents at the clinic in their hometown to be seen by a provider in the “big town up the road” (which was oftentimes 30, 40 minutes away, one way). I’ve also implemented a couple of A3-P scenarios for nursing home residents to have easier access to care.

Which 3 of the 96 scenarios are your most common video telemedicine scenarios? Post your insights in the comments below.

To receive articles like these in your Inbox every week, you can subscribe to Christian’s Telehealth Tuesday Newsletter.

Christian Milaster and his team optimize Telehealth Services for health systems and physician practices. Christian is the Founder and President of Ingenium Digital Health Advisors where he and his expert consortium partner with healthcare leaders to enable the delivery of extraordinary care.

Contact Christian by phone or text at 657-464-3648, via email, or video chat.